Bradley Cooper is proving his talent extends beyond acting – he’s also a skilled director. Bradley Cooper’s newest endeavor, “Maestro,” delves into the complex relationship between Leonard Bernstein and Felicia Montealegre. In a unique move, Cooper not only directs the biographical drama but also graces the screen in the lead role. Backed by heavyweight producers Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg, the film features an impressive cast, including Carey Mulligan portraying Felicia Montealegre, along with talents like Matt Bomer, Maya Hawke, and Michael Urie. The project promises to be an enthralling cinematic journey with a stellar lineup bringing it to life.

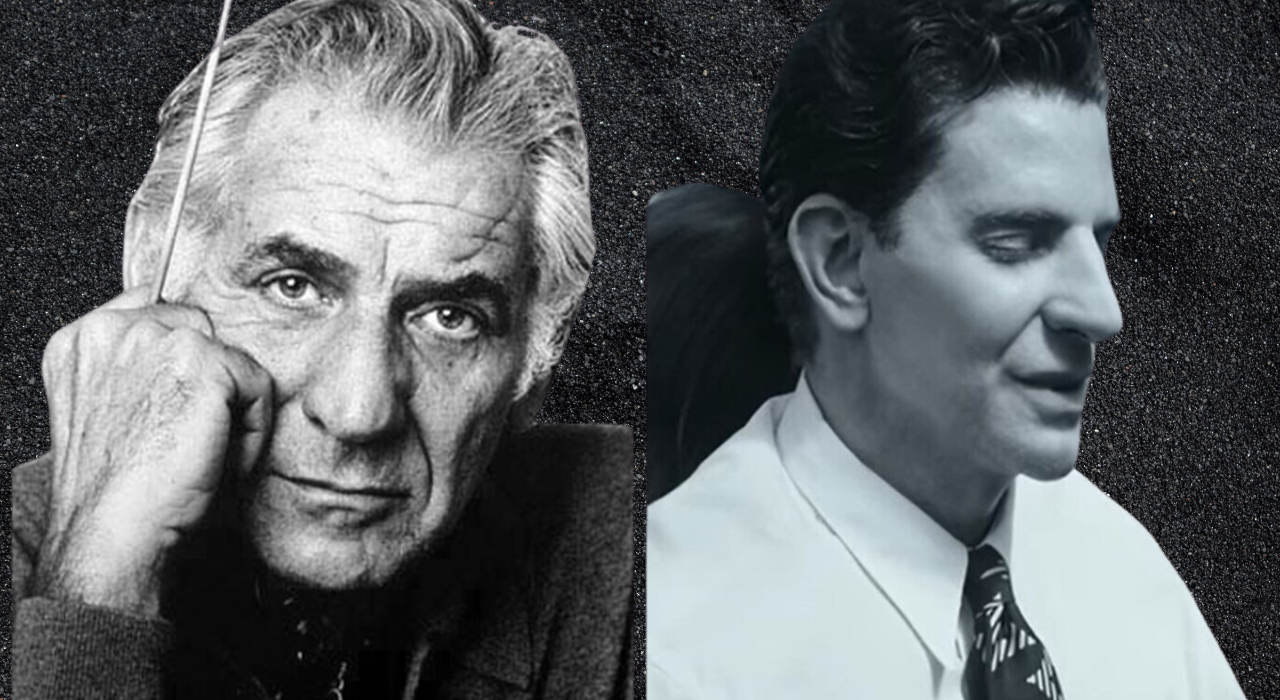

Leonard Bernstein, a true legend, was not only a renowned conductor and pianist but also a prolific composer. Leonard Bernstein stands tall in the annals of music history, earning recognition as one of the most impactful and talented conductors of all time. A trailblazer, he etched his name in history as the first American-born conductor to helm a major symphony orchestra. His illustrious career encompasses iconic compositions such as West Side Story, the original score for Elia Kazan’s film On the Waterfront, and three symphonies crafted with his own artistic brilliance. His contributions have left an indelible mark on the world of classical music.

Over the course of his illustrious career, Leonard Bernstein amassed an impressive collection of accolades, including two Tonys, seven Emmys, and a remarkable 16 Grammys. Notably, he also secured an Academy Award nomination. Beyond the realm of awards, his influence extended far and wide. Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts with the New York Philharmonic stood as a testament to his commitment to bringing classical music to a wider audience, captivating viewers through televised programs. His impact resonated deeply in both the world of music and popular culture.

In contrast, Felicia Montealegre carved her own path as a distinguished actress, leaving an indelible mark with captivating performances on both television and the stage. Her success spanned Broadway productions to appearances at the Metropolitan Opera. As a dynamic duo, Leonard Bernstein and Felicia Montealegre stood as a formidable power couple, making substantial contributions to the realms of music and the performing arts. Together, their artistic endeavors left a lasting legacy that resonates in both spheres.

Even though Leonard Bernstein and Felicia Montealegre tied the knot in 1951, the movie reveals that their marriage wasn’t all smooth sailing. While their public image portrayed a picture-perfect couple, the film peels back the layers to reveal the persistent challenges that defined their relationship. As is often the case with biographical films, viewers are intrigued by the true-life story behind this iconic couple. The genuine narrative of Bernstein and Montealegre’s relationship unfolds, offering a glimpse into the complexities that might not have been readily apparent in their carefully crafted public image.

Encounter of the Maestros: Unraveling the Story of Leonard Bernstein and Felicia Montealegre’s Meeting

The story of Bernstein and Montealegre began in 1946 when they first met at a party hosted by pianist Claudio Arrau. Despite getting engaged a few months later, their journey hit a bump, leading to the end of their engagement. Following this, Montealegre entered into a relationship with actor Richard Hart, and they shared their lives until his passing in 1951.

However, fate had other plans. Bernstein and Montealegre found their way back to each other, rekindling their romance. On September 9, 1951, in Boston, they sealed their love with marriage, marking a significant chapter in their tumultuous but enduring relationship.

Symphony of Love: Leonard Bernstein and Felicia Montealegre’s Marriage Unveiled

Bernstein and Montealegre built their life together, residing between New York City and Connecticut, and they were blessed with three children. Their homes were a hub of social activity, hosting gatherings that attracted the crème de la crème of composers, playwrights, and writers of their era.

While Bernstein projected devotion to Montealegre in public, the truth behind their marriage was more complex. Behind closed doors, the celebrated composer was involved in multiple affairs with both men and women while still married. Montealegre, reportedly aware of Bernstein’s infidelity even before they tied the knot, carried the weight of this knowledge throughout the years. It adds a layer of complexity to the public image of their seemingly glamorous life.

Despite the challenges in their personal lives, Leonard Bernstein and Felicia Montealegre found common ground in their professional pursuits. Both were dedicated to their careers and shared a passion for supporting various causes, including the civil rights movement, the anti-war movement, and other humanitarian organizations.

In 1965, Bernstein took part in the Stars for Freedom Rally, a concert organized by Harry Belafonte, aimed at inspiring the Selma marchers to continue their historic walk. Meanwhile, in 1974, Montealegre collaborated on a report about the New York State parole system with Coretta Scott King, Victor Marrero, and other members of the Citizens’ Inquiry on Parole and Criminal Justice, Inc. Their shared commitment to social causes reflected another side of their dynamic partnership beyond the public eye.

leonardbernstein.com reveals that Bernstein struggled with his sexuality and reportedly sought therapy to address it, attempting to “cure himself.” In a poignant letter to his sister, Bernstein admitted, “I have been engaged in an imaginary life with Felicia.”

The turning point came in 1971 when Bernstein crossed paths with Tom Cothran, a music scholar and the music director of a San Francisco radio station. Their connection deepened into a relationship, and by 1976, Bernstein made the decision to leave Montealegre and relocate to California to live with Cothran. It marked a significant chapter in Bernstein’s personal journey and the evolution of his relationships.

What transpired in the life of Felicia Montealegre?

In 1977, Montealegre faced a challenging battle with lung cancer. Bernstein, despite the complexities in their relationship, came back to be by her side. He took on the role of caretaker, providing support and comfort until she ultimately passed away in 1978. It was a poignant and undoubtedly difficult chapter in their shared history.

What transpired in the life of Leonard Bernstein?

Bernstein’s dedication to music endured even after the events of his personal life. He continued to compose and conduct until he officially retired in 1990. Tragically, on October 14, 1990, he succumbed to a heart attack, a consequence of his longtime struggles with smoking and emphysema. His final resting place is in the Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, where he lies alongside Montealegre, marking the end of a prolific era in the world of music.

How About the Schnoz?

For those who might have missed the internet buzz over the last six months, a bit of a commotion stirred up when the first images from the film surfaced. Bradley Cooper, portraying Bernstein, was seen with a notably prominent prosthetic nose. Some raised concerns, suggesting it might perpetuate stereotypes about Jewish features.

Interestingly, the nose in question is pretty much the same size as Bernstein’s actual nose. However, the hitch is that Bernstein had a different facial structure. To add a bit of personal opinion, as a young man, Bernstein was arguably more handsome than Cooper (minus the actor’s imposing physique), so his nose didn’t seem as out of place as it appears on Cooper. Strangely, the nose seems less conspicuous as Cooper transitions into portraying the older Bernstein, possibly because the aging makeup evens things out a bit. It’s a quirky aspect of the film’s portrayal that caught the attention of many onlookers.

Did the Bernsteins’ Love Story Truly Live Up to the Public Image?

As Felicia (Carey Mulligan) and Lenny delve deeper into their connection, it becomes evident that they genuinely enjoy each other’s company and share a profound connection. Lenny enthusiastically introduces her to his circle of friends, and Felicia broaches the topic of marriage, expressing her willingness to accept him as he is—without the need for martyrdom. She suggests, “Let’s see what happens if you are free to do as you like, but without guilt and confession.” Her only request is for him to be discreet and avoid embarrassing her.

However, things take a turn when, in Felicia’s words, Lenny gets a bit “sloppy” in middle age, openly carrying on with a younger man. It’s at this point that Felicia decides to kick him out, leading to their separation. This twist in their relationship adds a layer of complexity to their story.

The fundamental aspects of their relationship and the arrangement they made hold true. Interestingly, it was Bernstein who proposed to Montealegre during a trip to Costa Rica. While it may not have been a whirlwind of passion, it appears that he genuinely loved her, as a heartfelt letter to his sister, Shirley, published in The Leonard Bernstein Letters, reveals. In the letter, he expressed, “How strange that you have written to me just now of Felicia! Ever since I left America she has occupied my thoughts uninterruptedly, and I have come to a fabulously clear realization of what she means—and has always meant—to me. I have loved her despite all the blocks that have consistently impaired my loving-mechanism, truly and deeply from the first. Lonely on the sea, my thoughts were only of her. Other girls (and/or boys) mean nothing.” This candid letter offers a glimpse into the depth of Bernstein’s feelings for Montealegre, dispelling any doubts about the sincerity of his love.

Shortly after their wedding, Felicia penned a letter to her new husband that laid bare the realities of their situation. She wrote, “You are a homosexual and may never change—you don’t admit to the possibility of a double life, but if your peace of mind, your health, your whole nervous system depends on a certain sexual pattern what can you do? I am willing to accept you as you are, without being a martyr or sacrificing myself on the L.B. altar. (I happen to love you very much—this may be a disease and if it is what better cure?) … The feelings you have for me will be clearer and easier to express—our marriage is not based on passion but on tenderness and mutual respect.” In this candid letter, Felicia confronts the realities of their relationship, acknowledging the challenges and setting the tone for a marriage built on understanding, tenderness, and mutual respect rather than traditional notions of passion.

The film, while capturing the essence of Bernstein and Montealegre’s relationship, skips over some pivotal moments. Contrary to the romantic narrative portrayed, Montealegre didn’t enter into the marriage swept off her feet but rather as a result of rebound. Their initial engagement in 1947 ended, and Montealegre found solace in a romance with actor Richard Hart (a scene in the film nods to this when Hart visits her Broadway dressing room). Despite her clear affection for Hart, she remained devoted to Bernstein. Tragically, Hart passed away in early 1951, prompting Montealegre to give Bernstein another chance.

This twist in their story, not fully depicted in the film, involves a second engagement in August 1951, leading to their marriage a month later. Meanwhile, during the interim period, Bernstein had a passionate romance with an Israeli soldier, Azariah Rapoport, from 1948 to 1949. The omissions from the film shed light on the complexities and nuances of their relationship that may not have made it to the big screen.

Maestro’s oversight

The film captures key aspects of Bernstein’s life, but there’s a notable omission—his impactful legacy as an educator through his enlightening TV programs on Omnibus and the Young People’s Concerts. In these shows, Bernstein skillfully delved into the worlds of rock, jazz, and 19th-century Viennese orchestral works, showcasing his versatility as a communicator.

While the movie portrays Bernstein as a conductor, composer, and lover, it overlooks what he fondly referred to as his “Lenny lectures.” These lectures were a significant part of his legacy, where he shared insights and lessons with a didactic quality inherited from his Talmud scholar father. Even simple phrases, like “Pass the salt,” would elicit lessons, such as the tale of Lot’s wife turning into salt. The absence of these enriching lectures in the film is a substantial oversight.

Bernstein was known for his vibrant social life, yet the film primarily centers on him and his wife, leaving little room to explore the creative individuals surrounding him. While key cultural figures like choreographer Jerome Robbins, actress Judy Holliday, and writers Betty Comden and Adolph Green make appearances, the film barely delves into their significance. Viewers are left in the dark about who these individuals were and what role they played in Bernstein’s life and work. It’s a missed opportunity to fully grasp the rich tapestry of relationships and collaborations that shaped Bernstein’s artistic journey.

The film barely touches on Bernstein’s left/liberal political engagements, a significant aspect of his life that profoundly impacted his public image. Wolfe’s satirical 1970 article, “Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny’s,” lampooned the Bernsteins’ fundraiser for the Black Panthers, yet the film downplays its consequences. Wolfe’s witty critique, featured in the recent Tom Wolfe documentary Radical Wolfe, mocked the lavish offerings to the Panthers, including Roquefort cheese morsels and meatballs petites au Coq Hardi served on silver platters by maids in black uniforms.

However, Wolfe’s satire, while brilliantly mocking, contained inaccuracies that the family spent years correcting. The film misses an opportunity to delve into the complexities of Bernstein’s political involvement and the fallout from events like the infamous fundraiser, providing a more comprehensive understanding of this facet of his life.

How the maestro plummeted from the sky

The devastating blow came in 1978 when Felicia succumbed to cancer. Bernstein, unable to bounce back, found himself in a downward spiral. His fame, grandiosity, and the distractions of a tumultuous life left him unable to cope without the support system he had grown accustomed to. Despite seeking solace in other lives and partners, Bernstein struggled to fill the void left by Felicia, and the challenges took a toll on his well-being.

One of my most vivid memories with Bernstein dates back to 1983 when I spent several hours interviewing him at the Dakota apartment house to mark his 65th birthday. It was a poignant experience, as he appeared profoundly sad and trapped within himself, revealing a side of Bernstein that hinted at the internal struggles he faced during that period.

Bernstein shared with me the profound shift in perspective that comes with age. At 30, he felt invincible, composing on the go during concert tours. However, by the time he reached 65, the transition from conducting to composing became a formidable challenge. The results sometimes fell short of his lofty standards. He explained, “The better you become as a conductor, the harder it is to change back into a composer. I stopped conducting at the end of September ’82, and I didn’t write one note that I could even look at the next morning without a jaundiced eye until November.” This candid revelation highlighted the evolving dynamics of his creative process over the years.

Despite his brilliance and the world’s gratitude toward him, Leonard Bernstein appeared to yearn for nothing more than an escape from the burdens of being himself. He coped with the turmoil by consuming several packs of cigarettes a day, often accompanied by gin. The documentary Maestro even includes footage of a cocaine party, a reflection of the drug’s prevalent use in the 1980s. Occasionally, he displayed shocking rudeness and engaged in maudlin public scenes. However, even in the midst of personal struggles, he continued to conduct with brilliance until the end. His ability to inspire students remained unwavering, earning their adoration for good reason.

Just days before his passing at the age of 72, Bernstein began crafting his own eulogy. It opened with the ironic line, “Cut down in the prime of his youth…” In a peculiar sense, he was expressing a truth about the inexorable passage of time and the poignant reflection on a life that, despite its brilliance and accomplishments, felt fleeting in its brevity.